Can the fashion industry clean its ‘dirty’ climate change hands

CAN THE FASHION INDUSTRY CLEAN ITS ‘DIRTY’ CLIMATE CHANGE HANDS

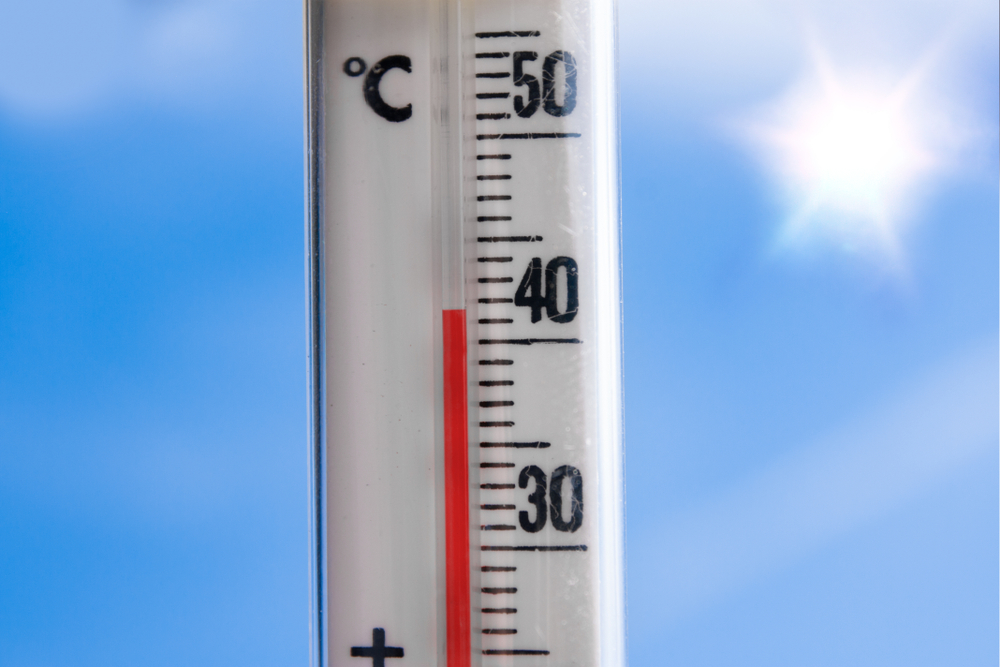

As the North Hemisphere swelters this August we're

left knowing the fashion industry has the dubious honour of contributing to the

planet's climate crisis, so what's next, asks Gherzi Textil Organisation

partner Robert P. Antoshak.

The debate over

climate change may have taken a turn this year as the North Hemisphere suffered

through a brutally hot July. In fact, according to the United Nations, “July has

already seen the hottest three-week period ever recorded; the

three hottest days on record; and the highest-ever ocean temperatures for this

time of year. The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling

has arrived. Climate change is here. It is terrifying. And it is just the

beginning,” reported the Washington Post.

As the North Hemisphere

swelters in August, we’re left knowing that our industry has the dubious honour

of contributing to the planet’s climate crisis. Over the past 40 years, our

industry built an intricate global system of suppliers, contractors, and

shippers, supported by a complex infrastructure of storage and logistical

services – all to maximise just-in-time retail replenishment and consumer

purchasing, the essence of fast fashion.

But over those same 40 years,

climate change became harder and harder to ignore or explain away. Politically,

governments and members of the polis have had an increasingly difficult time

ignoring this changing world. Indeed, scientific evidence documents that

warming waters, droughts, intense weather events, runaway wildfires, and

melting ice caps are not a figment of the imagination of overzealous

environmentalists – but are real.

The fashion industry has

dirty climate change hands

And our industry has

contributed to our warming world. The rush to globalise resulted in more energy

consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and pollution of our water resources.

Our industry’s logistical efficiency in managing a global network of suppliers

and logistical systems is something to behold. Please make no mistake: it’s an

outstanding achievement but costly considering our industry’s impact on the

planet’s climate. In this sense, efficiency went hand in hand with

environmental indifference.

A small consolation is that

our industry isn’t solely to blame for climate change. But as a significant

contributor, our hands are dirty. We have a responsibility. Yet, our industry

has increasingly come to grips with its environmental responsibilities. There

are genuine efforts to change business practices, find ways to repair the

damage if possible, and work towards a more plant-friendly future.

Even so, as an industry

dominated by marketers, new environmentally-friendly initiatives are often

tainted with marketing spin (think sustainability, circularity, or even

transparency). In some ways, it’s unavoidable as change takes time; innovation

is not a straight-line endeavor but rather a process typified by fits and

starts, failures and successes. As it took years for globalised supply chains

to emerge, it will take time for many aspirational environmental goals to be

realised.

The rub is if future goals of

achieving sustainable objectives are put off until 2030, 2040, or beyond. It

sounds great as a message for today – only who will be around to remember it in

15 years? A marketer’s delight to sell for today with a story for tomorrow;

whether it’s true or not is irrelevant as long as the next quarter’s sales

goals are hit.

The world’s great

broiling

The summer is often a time to

read books on the beach or at the pool and take a break from the grind. Only

this year, it’s too hot to sit by the pool. After all, as the UN’s metrological

chief said recently: “The era of great broiling has arrived.”

So what should our industry do

confronting a changing global environment? There are many suggestions, for

sure. But a rallying cry of some environmentalists is for consumers to buy less

(and recycle more). The assumption is that by consuming less, there will be

less post-industrial waste and less post-consumer waste in landfills or burned.

If demand eases, the demand for environmentally harsh raw materials will also

reduce, or so the thinking goes.

Of course, this flies in the

face of the realities of an industry built upon the foundation of cheap stuff

made possible by vast scales of production. If consumers buy less stuff, then

what? And if they buy less, do low prices lose their appeal? After all, if

people don’t want to buy, then isn’t the allure of low prices somehow muted?

Is this the end of

cheap fashion to combat climate change?

That could be the case but for

various reasons, including changes in sourcing, consumer attitudes, and

demographics. Claims from the Wall Street Journal: “The twilight of

ultracheap Asian factory labour is emerging as the latest test of the globalised

manufacturing model, which over the past three decades has delivered a vast

array of inexpensively produced goods to consumers around the world. Americans

accustomed to bargain-rate fashion and flat-screen TVs might soon be reckoning

with higher prices.”

Why? There are several

reasons, but most pointedly, there is a shortage of young workers, particularly

in China. Demographic changes have played a role as many families have fewer

children than was the case with previous generations. Expectations also affect

employment: many young people want to work in service or technology jobs rather

than manufacturing.

Further, China has graduated

record numbers of young people from universities only to find relatively few

jobs for well-educated individuals. Manufacturing jobs, in turn, don’t even

register for many of these recent graduates despite recent calls by Beijing for

schools to lower the expectations of new entries into the workforce. How will

our industry adapt without China in the mix to make lots of stuff with good

quality and low prices? China’s costs began to rise even before the pandemic.

Globalised economics is

predicated on continued growth. That’s why so many international organisations

fret over global growth forecasts. But what happens if people say they have

enough stuff? Does price really matter, then? And could that be more than just

a temporary occurrence? In the West, the population is getting older – so do

they really need so much stuff?

What’s the bottom line for

clothing companies? The age of inexpensive goods may be coming to an end. For

consumers long accustomed to dirt-cheap clothing, a day of reckoning may be

around the corner. For fast fashion companies, you may have to get faster – or

learn how to sell less but accept a mark-up.

Is less demand a

good thing for fashion and climate change?

There is a curious thing to

consider, though. If prices go up due to changes in Asian supply chains,

consumption will presumably go down. In turn, will over-consumption by

consumers moderate? It’s not a great development for brands and retailers – but

some environmentalists would welcome it!

Our industry was built for a

different time. High growth and over-consumption were the pillars of the

industry. Today, it’s a new ballgame. But, as we’ve seen with so many

environmental programmes, the party got out of hand. We’re in a hangover. Less

consumption is the order of the day, either because of consumer conviction or

economics.

Nevertheless, there’s also so

much fashion supply out there – and this is where we see the intersection of

free markets and climate change. Too much of a good thing has left us to pay

the bill, with the planet stuck with the tab.